- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

The Origin of Party Politics in America: Jefferson vs Hamilton

Jefferson - Hamilton Rivalry

Jefferson vs Hamilton: The Origin of Party Politics in the U.S.A.

By Michael M. Nakade

(The following is an imaginary dialogue between a political science professor and an A.P. U.S. History student.)

Student: Professor, I was watching the news the other day on C.N.N. and heard one gentleman saying that today’s leaders are politicians who only care about winning the upcoming election. We no longer have statesmen.

Professor: That’s an interesting comment. I can think of George Washington being the true statesman, but others? Not so sure.

Student: Just Washington? How about other Founding Fathers? Weren’t they statesmen?

Professor: Well, it’s a matter of opinion. But, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, and Hamilton were all politicians. They cared deeply about elections and attacked their political enemies ferociously. Sometimes, they flip-flopped when it was politically convenient to do so. They are not that different from the politicians of the 21st century. It’s really not easy to be true statesmen when they have to get elected by the public to practice political leadership.

Student: I guess I have an idealized view of America’s Founding Fathers. Will you tell me more about them in terms of their being politicians?

Professor: Let me quote the Dictionary.com’s definition of the word, “politician.” It says: “a seeker or holder of public office, who is more concerned about winning favor or retaining power than about maintaining principles.” Jefferson, for example, insisted on the principle of a weak central government when he was fighting the Federalist Party leaders. But, he did his political 180 when he became the president. He expanded the power of the presidency in order to make a deal with Napoleon for the purchase of Louisiana Territory. It’s just one example among many.

Student: But, it doesn’t mean that Jefferson was always a politician, does it? He did his political 180 because he believed that it was in the best interest of the United States. Right?

Professor: That’s right. It wasn’t like Jefferson’s only concern was about holding on to his power. He cared deeply about the United States and made decisions based on his visions for the future of America. But, he was almost always opposed by the Federalists like Adams and Hamilton. Sometimes, politics got ugly. Personal smears were common already in the late 1700s. The party politics in the United States back then was just as nasty as what we get in the 21st century.

Student: So, what kind of visions did the Federalists have? What did they dislike about Jefferson’s visions?

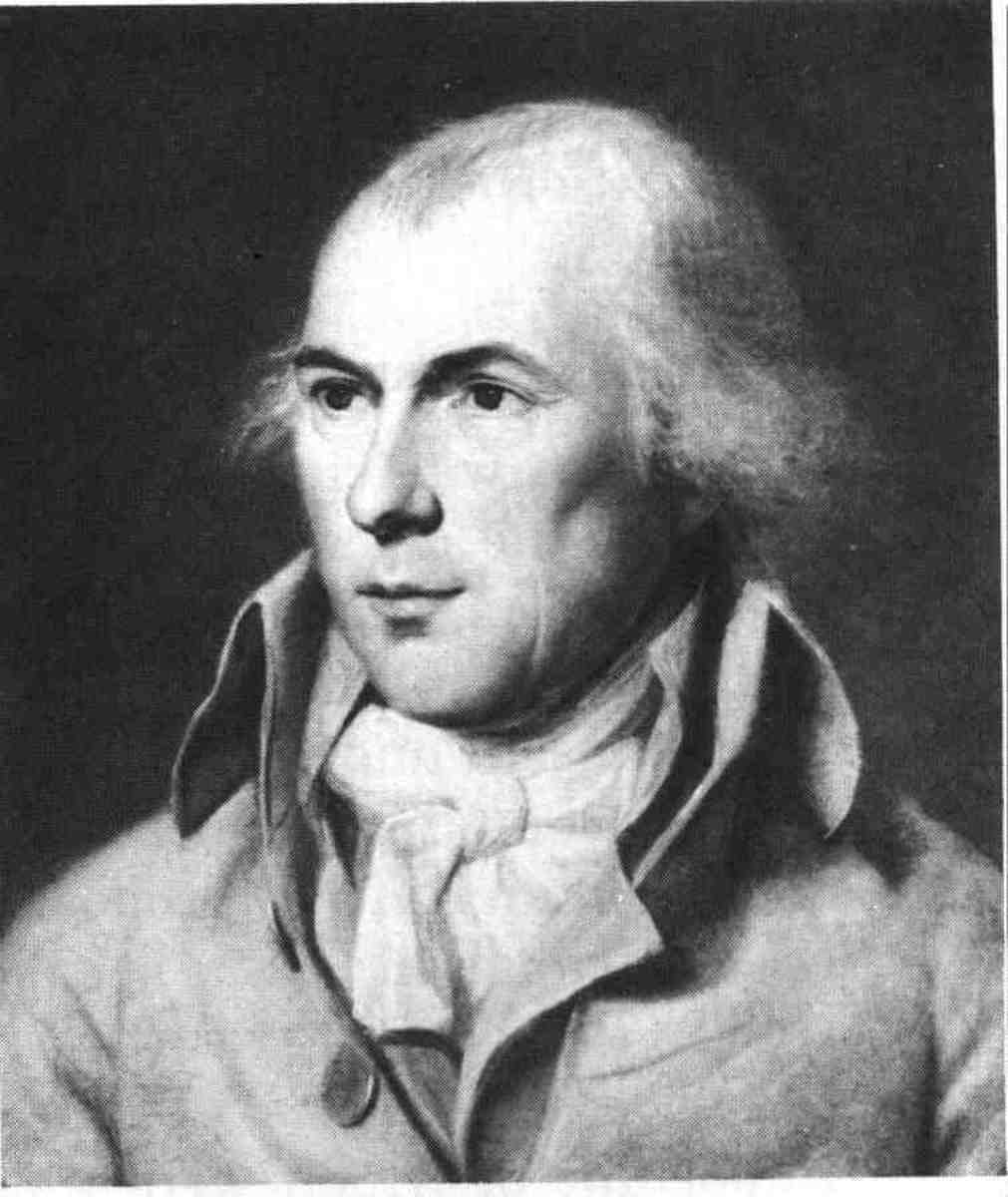

Professor: I would just focus on Hamilton, the first Secretary of Treasure in the Washington Administration. Hamilton was a pro British monarchy, pro big businesses, pro strong central government, and activist federal government. He was everything Jefferson was not. Knowing how it is today, it is impossible to imagine that he served in the same cabinet with Jefferson. Their visions were almost always polar opposite.

Student: So, Jefferson was anti British monarchy, anti big businesses, anti strong central government, and anti activist federal government.

Professor: Well, let me say that Jefferson preferred the French style Republic to the British Monarchy. Instead of saying anti this, and anti that, I’d like to say that Jefferson believed that the government was created to ensure people’s liberty. He did not want the federal government to interfere with affairs of state governments. His vision for America was that of agrarian society where people could become independent farmers and be self-sufficient. Without a doubt, he hated Hamilton’s Bank of the US that helped the businesses in big cities.

Student: But, like you said, Jefferson did his political 180 when he wanted to close the deal with Napoleon, right? Do you think that was a black eye for Jefferson?

Professor: No, not at all. If anything, that’s Jefferson’s finest hour as the president of the United States. He doubled the size of the United States with a stroke of his pen. Certainly, he risked being called a hypocrite for going ahead with the Louisiana Purchase because he expanded the role of the federal government in the process. But, so what? That was a small price for the benefit of the entire nation.

Student: Any other incidents or examples of political 180 from that era?

Professor: Good question. Let’s focus on the Federalist Party. When Adams was the president, he was paranoid of radical French revolutionary ideas. He and the congressed passed the legislation called the Alien and Sedition Act of 1798, severely restricting the freedom of speech and of the press. Jefferson was furious, even though he was Adams’ vice president. He and Madison secretly got together and argued for the state’s right to nullify federal laws, which each state deems unlawful. It is known as the Virginia and Kentucky Resolution. Hamilton and other Federalists vowed a forceful solution to this rebellion on the part of the State of Virginia. It was the first known debate over the states’ rights versus the power of the Federal government. The Federalists were adamant about the supreme power of their federal government. But, they did their political 180 in 1814 to protest the Federal government’s decision to have a war against Britain during the war of 1812. The Federalists in New England area known as the Essex Junta openly discussed the secession from the Union and insisted the states’ rights.

Student: Interesting. Political parties can change their so called principles when deemed necessary. Right?

Professor: That’s right. Politics is the game of who gets what, and how. The Federalists wanted to get what they wanted and were willing to change their stance. Jefferson did the same.

Student: So, does this mean ‘integrity’ is difficult in politics?

Professor: Very difficult. Political parties have their respective platform and do their best to achieve them. But circumstances change, and what they insisted before must change also. If they flip-flop too often, then, they lose their credibility, but a change of a direction here and there can be forgiven.

Student: I want to know more about the Secretary of Treasure, Hamilton. He’s on our $10 bill. But, the guy never became president. Why was he so important?

Professor: Hamilton was a kind of man whom you loved to hate because of his brilliance and arrogance. He was incredibly smart, and he knew it. He didn’t have enough charisma to be president of the United States, but he was Washington’s trusted lieutenant since the days in the Continental Army. He was the most influential Federalist at that time and was Jefferson’s political rival in every sense of the word. He was killed by Jefferson’s vice president Aaron Burr in a duel in 1804.

Student: What about Hamilton’s policy? What did he push for, other than the Bank of the United States?

Professor: Hamilton wanted to expand the power of the federal government over state governments. The first thing he did was to propose that the Federal government ‘assumes’ the debt of each statement government. But his idea met with fierce opposition from southern states that didn’t have any debt. So, he did his bargaining. He promised southern state the nation’s future capital city in exchange for having them agree to the Federal government’s assumption of states’ debts. That’s how Washington D.C. found its way in the South. He also wanted the federal government to have the power to tax directly in order to raise necessary funds for strong national military forces. How do you think that Jefferson responded to Hamilton’s policy?

Student: I bet Jefferson hated every single one of Hamilton’s idea.

Professor: You bet. Jefferson wanted the federal government to be small, weak, and non-intrusive to the affairs of people. In his mind, the federal tax must be as low as possible. In other words, Jefferson really believed that the government that did the least was the best because he was afraid that the government might interfere with people’s liberty.

Student: I see. Things that Hamilton and Jefferson argued for sound a lot like what we hear today between the two major political parties. They, too, argue what the federal government should do and shouldn’t do.

Professor: Yes. Very good observation. As long as we have a party politics, we will continue to debate how the government of the United States should be. Do we want a big government with tons of social programs, but in exchange, we accept a higher tax rate? Or, do we want a small government that does not offer as many social programs, but in exchange, we pay less tax? Or, do we want a huge military force supported by a high tax rate? Such discussions continue to this day.

Student: Finally, what did George Washington think of Hamilton-Jefferson rivalry within his cabinet?

Professor: Actually, Washington listened to Hamilton rather than Jefferson. But, it is well known that Washington warned of America’s party politics in his farewell address to the nation in 1796. He wanted to act above party politics, and to a large extend, and to that end, he succeeded. But his successors had to play party politics because that’s what the political system called democracy demanded. Remember: politics is a game of who gets what and how. Sometimes, politicians have to discredit their opponents in order to get what they want. It’s up to them to decide how ‘nasty’ they want to be in the process. The election of 1800 was nasty. It’s a good thing that George Washington didn’t live long enough to experience it. He would have hated it.

Student: Thank you, professor for explaining party politics from the late 1700s. I learned a lot about Hamilton and Jefferson rivalries. Their arguments don’t seem that different from today’s political debates.

Professor: I’m glad that you can see it like that. It’s very much so.

(Information indicated in this work came from The Teaching Company’s Lecture Series on the United States History, 1st edition, Part III: The Making of a Nation, Lecture 25, “Federalists vs. Republicans” by Louis Masur, Ph.D.1998)